Duck Cannons of the Chesapeake – When Punt Guns Spoke, Waterfowl Markets Sang

- Ken Perrotte

- Nov 18, 2020

- 5 min read

Updated: Sep 7, 2021

Imagine a time when nighttime duck assassins stealthily maneuvered low-profile skiffs toward vast rafts of dozing ducks and geese, blasting them at close range with punt guns -- massive, heavy, boat-mounted duck cannons.

The late Harry N. Walsh, out of necessity a Maryland Eastern Shore outlaw gunner in his youth and later a physician and author, called the era of the big guns the, “greatest, most dangerous and most demanding method of wildfowling.” Market hunters seeking optimum killing efficiency slayed dozens of birds with a single shot.

How lucrative could it be? In his landmark book, “The Outlaw Gunner,” (1971 by Tidewater Publishers) Walsh recounts an interview with four aging market hunters who gunned the Holland Island area. One night, working as a team with each having a punt gun, they executed four simultaneous shots. Walsh quoted Ray Todd of Cambridge, Maryland, as stating “By morning, we had killed over a thousand ducks; they brought $3.50 a pair in Baltimore and it was the best night’s work we’d ever done.” A single gunner routinely could kill 50 to 70 birds in an evening with just a shot or two. Gunners often teamed up, shooting the rafted flocks at varied angles to up the kill count.

Heavyweights

The guns were named for the type of small, flat-bottomed skiff in which they were used.

Pete Lesher, curator of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum in St. Michaels, Maryland, said punt guns were not created equally.

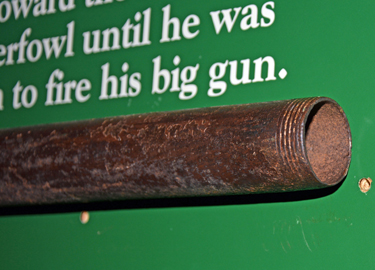

“The bores, the length of barrels, the weight and more is all over the map. I haven’t seen two the same,” Lesher said. Some gunners had heavy, well-machined varieties with barrels made at foundries equally suited to producing cannons. Other versions were largely homemade jobs, crafted using high-pressure pipe tapped to accept a hammer lock. Ignition systems began as flintlocks, but some guns were later converted to fire with percussion caps. Bores two inches in diameter on some of the bigger guns could launch an incredible spray of shot. Some of these large production guns could weigh nearly 200 pounds.

The heaviest guns were typically manufactured in England. Other production guns came from Washington or New York. Lesher said he has heard stories of a few punt guns being made at the Naval Gun Factory at the Washington Navy Yard in “after hours, unofficial” labors.

“These guns would’ve been well-crafted,” he said, adding, “They probably fitted out barrels made as naval guns with the stock and firing mechanism needed for a punt gun.” Lesher said some gunners likely would’ve ordered factory-made punt guns from European manufacturers through high-end hardware stores. He wasn’t certain what manufactured guns would cost, but bet it was pricey, given the investment return. With a brace of ducks fetching a couple bucks, gunners filling customer orders could make considerable fast cash with a couple shots.

Walsh wrote that the earliest punt gunners were sailors used to firing cannons aboard ships. They knew how to handle the recoil that comes when launching two pounds of lead shot.

“Virtually any extremely oversized bore might have been called a punt gun,” Lesher said. “Anything below 4 gauge was usually used as a boat gun, either mounted to or rested in a boat for firing.”

While the actual diameter of the guns’ bores might be similar, their barrel-wall diameters could vary significantly. For example, the gun on display at the Maritime Museum is likely an industry-produced piece, possibly from England. The steel at the muzzle is about ¼-inch thick. Comparatively, the guns on display at the Upper Bay Museum in North East, Maryland and the Ward Brothers Museum of Wildfowl Art in Salisbury are lighter versions fashioned from heavy pipe. The threading at the end of the pipe is even visible at the muzzle of the Ward Museum’s gun. These “Pipe Guns” became more common after extremely large bore guns became illegal and confiscations for their use increased. Still, some people refer to these as punt guns since they were often nearly as big as the production guns.

The Set-Up

The “sneak skiff” punt was typically 16-18 feet long and about 40-48 inches wide. Most were painted white, according to Walsh.

Walsh had several photos and explanations covering how boats and guns were deployed. The gun’s heavy wood stock rested firmly on a couple bags of sea oats to help absorb recoil. The barrel rested in a notched chock at the skiff’s bow, the barrel extended a few inches over the water. Another chock was positioned about hallway down the barrel.

Recoil was severe! A gunner needed at least four feet open behind the gun. Guns mounted too close to the stern could blast rearward through the wood, damaging or sinking the craft.

The gunner laid on his stomach and used hand paddles to silently maneuver toward the birds, often keying in on their vocalizations. Walsh said most shooting was right at the edge of dark, just before daybreak or as the moon was rising. The gun rested under the shooter’s shoulder.

Rick Bouchelle, the Upper Bay Museum’s president, dispensed with the myth that some market gunners loaded guns with everything from scrap metal to glass. “Why would they?” he said. “Shot was cheap (about 6 cents a pound/powder was a dime). Putting harder items in the gun would’ve damaged the gun’s barrel and torn apart the waterfowl. Everything they shot, they sold. This was their livelihood in the wintertime. They couldn’t afford to damage the ducks.” The actual load was a hefty measure of powder, some wadding, the lead shot, then more wadding. Bouchelle said some gunners reportedly used material from bee and hornet nests as wadding, while Walsh writes of oakum, which is old rope teased apart, being used over cork as wadding.

The Ban

The United States by the Migratory Bird Treat of 1918, which took effect in 1920, outlawed punt guns, Lesher said. Some places had already banned them. For example, Maryland regulations prohibited them from the Susquehanna Flats at the northern end the Chesapeake.

Lesher said he’s unaware of any authoritative estimates of the number of punt gunners around the Chesapeake, noting, “There wasn’t any way to do a reliable census.” Walsh’s book has a 1914 inventory showing 15 owners in the Susquehanna Flats area. The guns weighed between 100-125 pounds, were about 12 feet long and had bore diameters ranging from 1.5-2 inches.

Today, few original punt guns remain. Some were hastily buried in marsh mud when it became apparent lawmen were responding after hearing a shot. Gunners caught with the guns saw them confiscated. Several confiscated guns, likely taken by Fish and Wildlife Service agents, resided in the basement of the Department of the Interior, Lesher said.

Nobody is sure when the final ducks were killed with a punt gun. The big guns likely were used the longest in the Chesapeake’s remote island areas where there were fewer people, prying eyes and law enforcement officers.

The waterfowl black market existed well past the 1920 law, likely until the 1950s or beyond in some places, Lesher said. By then, though, outlaw gunners didn’t need punt guns. Lighter and less logistically challenging semiautomatic shotguns made shooting easier. Outlaws could still collect dozens of birds on good days.

Authentic punt guns are highly collectible and nearly impossible to find. Randy Birch, a waterfowl hunting guide and waterman from Chincoteague, Virginia, says he has made four replicas, keeping one and selling the others. Tim Kuca, a retired federal agent and now waterfowl carver from Fredericksburg, Virginia, bought one. Kuca collects antique big bore shotguns and other waterfowling memorabilia. Kuca said he periodically loads his with powder and paper. It makes for an entertaining “boom” with the right audience.

Comments